Reading Tadpoles

Slow moving time, hungry water, and all possible futures.

Every summer, for a month, my grandfather disappeared to Lasher Brook, the family hunting camp in Pennsylvania. He returned with stories of days spent fly-fishing, finding fawns tucked away in tall grass, and of bear that prowled for snacks in the middle of the night. Even in elementary school, I knew I wanted to go someday. Yet, I was shocked and then exuberant when my grandfather showed me two plane tickets and told me I needed to pack. We were leaving the next day for Lasher Brook and a third grader should get to spend a summer in the woods.

I have a thousand memories from that summer. My uncles and cousins came with their orange & white Brittany spaniel. And for a while, I was accompanied everywhere I explored and given a primer and what I could and could not touch. Then the rest of my family went back to their responsibilities and my grandfather and I were at camp alone.

I spent the days alone in the woods while my grandfather fished, gathering wild strawberries, and turning over rocks to look for brightly colored salamanders. I caught fireflies in a jar, but only once. To a girl from California, they were utter magic, but that magic died when they were trapped behind glass. I preferred to chase them through the clearing at the first glimmers of their nocturnal dance, my arms outstretched, entreating them to light on my fingers. What I loved the most though was the tadpoles.

The year before my summer at Lasher Brook, a tornado hopped through the woods and changed the course of the brook for a small stretch. My grandfather showed me where the water had jumped and a remnant pond that had been left behind. It was teeming with tadpoles, and my grandfather explained that while they looked like fish, they were all going to transform into frogs.

I spent days at the edge of that pond, watching the little tadpoles grow legs and then lose their tails. I don’t remember, but I have to imagine, that I was covered in mosquito bites. Yet nothing could get me away from the edge of the water. The world moves so slowly when you’re 8-years-old. It hard to imagine that you’ll ever grow up, even as you yearn to know who you will become and the possibilities that await. Yet, at the pond where Lasher Brook had unexpectedly been wrenched from its chosen path, I didn’t have to imagine what it was like to turn into something wholly new. The tadpoles transformed before my eyes. Deep in the woods, staring at the glassy surface of the pond, I could read all possible futures in the swirling of tadpoles beneath.

I don’t see frogs often. The edge of the desert where I live doesn’t tend to be hospitable to amphibians. So, I am always thrilled to stumble on riparian habitat with enough shallow water to welcome frogs. I just never expected to find an army of them a mile from my house.

Like the rare tornado that gave Lasher Brook a change of scenery, Tropical Storm Hillary changed the face of the San Gorgonio River near my house last year. We are generous with what we call a river in Southern California. Mostly what we mean is a dry riverbed that on occasion flows down from the mountains. It’s usually a trickle when it runs, only gorging itself a few days a time, lazily stretching to reach its phantom banks.

Hillary was an incredibly rare Southern California tropical storm, and I watched the San Gorgonio River gorge to what I thought were its banks and far beyond. Boulders as big as golf carts careened downstream crashing thunderously as they incised the riverbed and reengineered the landscape. The river roared and shook the ground beneath my feet, enveloping me in the purest form of awe, the kind that at its core is fear. Hydrological engineers call this “hungry water”. The water was ravenous. I’ll never be dismissive about the San Gorgonio being a river again.

A year later, with some help from a wet winter, it’s August and the San G. is still flowing heartily. Water always eats more than it can stomach and so there isn’t just a water source, there is rich soil where the river dropped sediment. It has become fertile with seep and sticky monkey flower, chia, penstemon, willows, cottonwood, and even one determined California fan palm. And where the boulders carved new paths, rivulets of water fill divots and depressions into ponds. I have never considered that something as old as river could transform itself into something wholly different, but it had. For the first time in 20 years, I discovered that I had tadpoles right down the street.

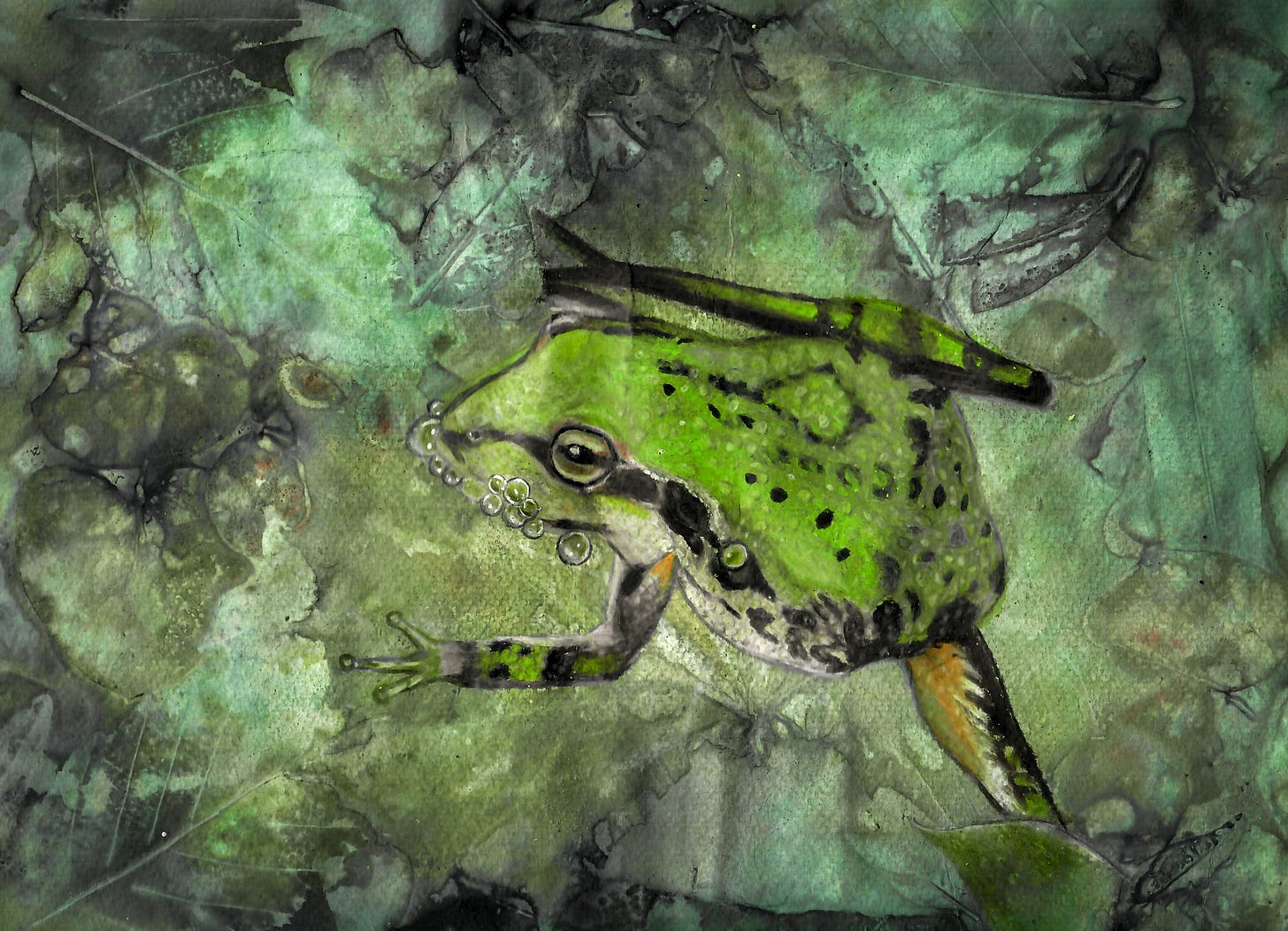

I told myself it was enough to just look at them and marvel over the cacophony of frogs, but I started wondering what species they were. I recognized the call. The were some sort of chorus frog, but were they Baja chorus frogs (Pseudacris hypochondriaca) or California chorus frogs (Pseudacris cadaverina). Maybe there were even some Rana frogs in there? I definitely saw a green frog. And before I knew it I had a tiny plastic cup in my hand and was anklet deep in tadpoles, scooping them up to get a look and catching frogs by hand.

I told myself it wasn’t a weird thing to be doing if I was only there for twenty minutes or so. Really, how many frogs could you catch, and how long could you stare at tadpoles until you’d had enough? Apparently, a lot longer than 20 minutes.

So, an hour and half later, as the sun was setting and the itch of mosquitos was rising, I took one last long look at the tadpoles, marveling over one maneuvering with its tail because it was not quite ready to try out its budding legs. For an hour and a half, I was an eight-year-girl catching frogs and nothing else mattered.

Time moves faster now than it did at Lasher Brook, and most days it seems too late in the game for amazing transformations. And yet, I keep returning to stare into the water where the tadpoles are transforming right before my eyes. And on the glassy surface above them, I can read all the possible futures.